Editor’s Note: In May 2020, the American Bar Association held its 34th Land Use Institute—an annual forum aimed at educating attorneys, planners, and government officials about recent developments in the law regarding zoning, permitting, property development, conservation, and environmental protection.

With the increasing use of drones to address many of these questions, as well as several well-publicized conflicts between local jurisdictions, property owners and drone pilots, Martindale-Hubbell preeminent-rated attorney Wendie Kellington of the Kellington Law Group, P.C. and pioneering drone expert Patrick Sherman of the Roswell Flight Test Crew prepared the following briefing for the conference.

The Insitu ScanEagle has seen extensive deployment by the United States armed forces and those of allied countries. However, it was also the first uncrewed aircraft system (UAS) to receive a type certification from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and has been approved for domestic operations in the Alaskan arctic conducted by ConocoPhillips.

In the United States, it is impossible to disentangle the laws and regulations that govern the use of small, civil uncrewed aircraft system (UAS)—otherwise known as drones—from the history that led to their creation. An understanding of one is impossible without an understanding of the other, as even the definition of common terms, such as “aircraft” and “drone,” have shifted throughout the creation of the current regulatory framework.

While larger, military-type UAS—such as the MQ-1 Predator and the Insitu ScanEagle—have operated and continue to operate in domestic airspace under special permission from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) granted to other federal agencies or large corporations, the regulations put in place over the past decade are focused almost entirely on UAS weighing less than 55 pounds, and often less than five pounds. These are the drones that appear most often in the popular media: small, battery-powered aircraft with four propellers and a gimbal-mounted camera—along with their fixed-wing cousins.

Drone Regulations Circa 1936

Although they would not have recognized it at the time, the first rules for the safe operation of civilian UAS were laid down by an organization founded in 1936—22 years before the FAA was established. The Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) was created to promote the nascent hobby of building and flying model airplanes, with a particular emphasis on preparing young people for careers in the fast-growing field of aviation.

The AMA continues to exist today, with nearly 200,000 members and more than 2,500 affiliated flying sites across the United States. To this day, its one-page safety code remains the bedrock for a diverse portfolio of activities ranging from drone racing to the operation of model aircraft powered by working jet turbines. Practiced in accordance with the AMA’s guidelines, model aviation has achieved an enviable safety record, with only six recorded fatal accidents in more than 80 years of flying.

Traditional aeromodeling has been viewed as so safe for so long that the FAA did not promulgate any significant rules and regulations to govern its activities for many decades. In 1981, the FAA did introduce an advisory document (AC 91-57) laying out a few common sense guidelines for model aviation that largely reflected the AMA’s own guidance to its members.

This system of self-regulation began to break down in the first decade of the new century. Enterprising hobbyists took existing model aviation components and paired them with wireless video transmission systems to create the first, primitive drones of the type that have become commonplace today. It quickly became apparent that these new systems had potential real-world applications never envisioned by either the FAA or the AMA, such as aerial photography and emergency response.

Furthermore, while traditional aeromodeling had largely been confined to flying fields affiliated with the AMA, the pilots of these home-built drones took their aircraft into places and situations where radio-controlled flight had never been contemplated: landmarks, public parks, events and festivals, and so on. It did not take long for these activities to evolve into commercial operations, as these pilots could provide aerial imaging at a tiny fraction of the cost of a conventional aircraft, or even in environments that would be impossible by any other means.

To guide their operations, these industry pioneers referred back to AC 91-57 and complied with its recommendations. The FAA viewed this as going well beyond the intention of the original advisory circular, so in 2007 the agency released docket number FAA-2006-25714, clearly stating that commercial operations were not permitted under the auspices of AC 91-57.

Headquartered in Muncie, Indiana, the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) and its 200,000 members have played a critical role in the development of uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS) regulations in the United States and continue to be actively engaged on topics such as Remote Identification (RID).

Twin brothers Walter and William Good were among the pioneers of radio-controlled aeromodeling and competed at the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) first national event, held in 1936.

FAA Prohibits UAS Operations

Effectively, the FAA’s action outlawed all private, commercial UAS operations in the United States. Public entities, such as a fire department or law enforcement agency, could seek a Certificate of Authorization (COA) from the FAA to permit limited operations, but these were difficult and time-consuming to acquire—and were not available to private individuals or businesses. Nevertheless, innovation continued among hobbyists and companies operating overseas, beyond the reach of US regulatory authorities.

Through these efforts, aircraft became more capable, more reliable and less expensive. In spite of the FAA’s blanket prohibition, commercial activities continued to expand, with some operators openly advertising their services on the Internet. Especially in film and television production, UAS operations were becoming increasingly common. By providing no legitimate means to permit such operations, the FAA had created a pressure vessel without an emergency relief valve—and the overwhelming market demand for this technology threatened to burst the regulatory framework meant to contain it.

When Congress passed the 2012 FAA Modernization and Reform Act (FMRA 2012), it opened the door to limited commercial operations in Section 333 of the law. It permitted the FAA to approve individual private operators on a case-by-case basis. However, it was 2014 before the agency actually took advantage of this clause and approved six “Section 333 exemptions” for aerial film crews based in Los Angeles.

The requirements to receive permission to operate under Section 333 were onerous. The person operating the drone had to be a licensed full-sized aircraft pilot and possess a Class 2 medical certificate—a standard even higher than is required for private pilots. Applicants for Section 333 exemptions had to submit voluminous paperwork related to their qualifications, maintenance procedures and safety protocols, and were limited to flights within a “sterile” environment on a movie or television production set.

Although Section 333 established a high standard—too high, in the estimation of many industry participants—it nevertheless provided a lawful avenue to conduct commercial UAS operations. Demand for Section 333 exemptions quickly spread beyond Hollywood to operators around the country interested in a portfolio of business opportunities beyond film and television production.

The Wilbur Wright Federal Building located on Independence Avenue in Washington, D.C., serves as the headquarters for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)—a role it shares with the nearby Orville Wright Federal Building. Much of the early work to support day-to-day drone operations, such as individual airspace authorizations, was performed at the agency’s headquarters.

Part 107: Rise of the Drones

FMRA 2012 also set a 2015 deadline for the FAA to achieve “full integration” of UAS into the National Airspace System (NAS)—a goal that has not yet been accomplished, nor will be in the foreseeable future. However, the agency has achieved several important milestones: none more significant than the establishment of 14 CFR Part 107 in 2016, which puts in place a regulatory framework for widespread deployment of commercial drones.

Part 107 establishes a clear set of rules for drone pilots to follow. Highlights include:

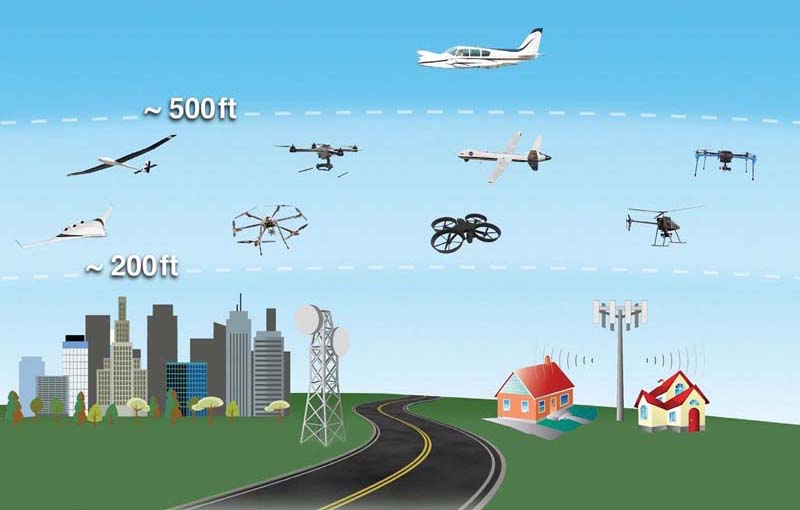

- No operations at an altitude higher than 400 feet above ground level

- No operations in excess of 100 miles per hour

- No operations of an aircraft weighing 55 pounds, or more

- No operations at night or with less than three statute miles of visibility

- No operations above persons not directly involved in the flight

- The aircraft must remain within the pilot’s visual line of sight at all times

- Pilot must only operate one aircraft at a time

- The UAS must yield the right of way to all other aircraft

- Operations in uncontrolled airspace are permitted without authorization

- Operations in controlled airspace are permitted with authorization

Part 107 also established a standard for the qualification of drone pilots: a 60-question Airman Knowledge Test (AKT) administered in a manner identical to private pilots and every other rating established by the FAA. Applicants must pass with a minimum score of 70 percent and must re-test every two years in order to keep their certification current.

Most critically, the FAA acknowledged UAS as “aircraft”—no different under the law from Cessnas and 737s—and their pilots as full members of the aviation community. However, this created a regulatory paradox that persists even today. If a drone is an aircraft, defined as “a device that is used or intended to be used for flight in the air,” then so is a model airplane.

In late 2015, the popularity of small drones like these prompted the FAA to use its emergency rule-making powers to establish a national system of UAS registration.

Drones and Model Airplanes

Complicating the matter further, in FMRA 2012, the AMA had achieved a long-standing goal of its lobbying efforts with Congress’s adoption of Section 336: the Special Rule for Model Aircraft. In short, it said that the FAA had no authority to create new rules governing model aircraft and shifting responsibility for their regulation to a community-based organization (CBO). Under the definitions in the law, only the AMA qualified as a CBO.

However, the FAA refused to acknowledge the AMA’s role as a CBO, arguing that the law did not define how a CBO would be formally recognized. This left the FAA as the sole arbiter of a critical distinction: between commercial and recreational operations. Ultimately, the FAA settled on a very broad definition of commercial operations, and a very narrow definition of recreational operations.

In essence, the FAA determined that UAS flights shall be considered commercial operations if they yield any benefit to any person, at the time of the flight or at any time in the future—regardless of whether or not money actually changes hands.

For example, if an unpaid search-and-rescue volunteer deploys a drone as part of a search for a lost hiker, that is a commercial operation because of the benefit to the hiker. If a farmer flies a UAS over her own fields to monitor the status of her crops, that is a commercial operation because those crops will eventually be sold for money. In theory, even capturing aerial video for fun and posting it on a personal Facebook page is a commercial operation, because Facebook will profit from the web traffic it generates. It is now settled, that to count as a recreational operation, a flight must be made purely for the enjoyment of the activity itself, in the moment it is occurring.

Going Backward

Not only has progress on UAS regulation been slow over the past decade, occasionally, it has even moved in reverse. One such example began in November 2015. Faced with the possibility of hundreds of thousands of new drones appearing under Christmas trees on the morning of December 25, the FAA used its emergency rule-making powers to establish a national system of UAS registration.

Under the system, all drone owners were required to visit an FAA website, pay a $5 registration fee and label their aircraft with a unique alphanumeric code. Failing to comply could result in a $27,500 civil penalty and criminal penalties up to $250,000 and three years in prison. Also, the regulation made no distinction between “drones” and “model airplanes,” so the traditional aeromodeling community was swept up in the effort, as well.

This action provoked a sharp response from the modeling community, centered on two key points: first, that the FAA had abused its emergency powers to sidestep the public comment period that is requisite in federal rule-making under the Administrative Procedures Act, and; second, the FAA was prohibited from putting in place new regulations affecting model aircraft under Section 336, the Special Rule for Model Aircraft. In spite of those protests, these registration regulations and penalties were put into effect and resulted in more than 700,000 registrations and allowing the FAA to take in more than $3.5 million from the new fee.

Opponents filed a lawsuit against the FAA, led by John Taylor—an attorney and drone enthusiast living in the Washington, D.C. area. In May 2017, an appeals court ruled in Taylor’s favor, holding that the FAA had indeed overstepped its authority and ran afoul of Section 336 in Taylor v. Huerta, 856 F.3d 1089 (2017).

Taylor’s victory proved to be short-lived, however. In January 2018, Congress enacted the National Defense Authorization Act, which included an amendment requiring all UAS to be registered with the FAA. With the requirement now written into law, it has become a permanent component within the industry. While registration remained unpopular with hobbyists, its reinstatement was welcomed by industry participants eager to see continued growth in the commercial use of drones. These included the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) and DJI, the world’s leading manufacturer of small, civil UAS, which saw registration as essential to the development of the market.

That same year, Congress passed the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (FRA 2018), which repealed Section 336 of FMRA 2012 and established in its place Section 349, giving the agency the explicit authority to regulate all UAS, including model aircraft flown for recreation. It also requires that all recreational UAS pilots pass an aeronautical knowledge test.

The test remains a work in progress as of this writing; however, early indications are that it will be much simpler than the test required to earn a certificate under Part 107, with the goal of insuring model aircraft and recreational drones do not interfere with the safe operation of manned aircraft.

Opening the Sky

With drone operations now a recognized component of the National Airspace System (NAS), the FAA began work to provide better access to airspace for remote pilots. The division In the United States, it is impossible to disentangle the laws and regulations that govern the use of small, civil uncrewed aircraft system (UAS)—otherwise known as drones—from the history that led to their creation. An understanding of one is impossible without an understanding of the other, as even the definition of common terms, such as “aircraft” and “drone,” have shifted throughout the creation of the current regulatory framework.

While larger, military-type UAS—such as the MQ-1 Predator and the Insitu ScanEagle—have operated and continue to operate in domestic airspace under special permission from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) granted to other federal agencies or large corporations, the regulations put in place over the past decade are focused almost entirely on UAS weighing less than 55 pounds, and often less than five pounds. These are the drones that appear most often in the popular media: small, battery-powered aircraft with four propellers and a gimbal-mounted camera—along with their fixed-wing cousins.

Drone Regulations Circa 1936

Although they would not have recognized it at the time, the first rules for the safe operation of civilian UAS were laid down by an organization founded in 1936—22 years before the FAA was established. The Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) was created to promote the nascent hobby of building and flying model airplanes, with a particular emphasis on preparing young people for careers in the fast-growing field of aviation.

The AMA continues to exist today, with nearly 200,000 members and more than 2,500 affiliated flying sites across the United States. To this day, its one-page safety code remains the bedrock for a diverse portfolio of activities ranging from drone racing to the operation of model aircraft powered by working jet turbines. Practiced in accordance with the AMA’s guidelines, model aviation has achieved an enviable safety record, with only six recorded fatal accidents in more than 80 years of flying.

Traditional aeromodeling has been viewed as so safe for so long that the FAA did not promulgate any significant rules and regulations to govern its activities for many decades. In 1981, the FAA did introduce an advisory document (AC 91-57) laying out a few common sense guidelines for model aviation that largely reflected the AMA’s own guidance to its members.

This system of self-regulation began to break down in the first decade of the new century. Enterprising hobbyists took existing model aviation components and paired them with wireless video transmission systems to create the first, primitive drones of the type that have become commonplace today. It quickly became apparent that these new systems had potential real-world applications never envisioned by either the FAA or the AMA, such as aerial photography and emergency response.

Furthermore, while traditional aeromodeling had largely been confined to flying fields affiliated with the AMA, the pilots of these home-built drones took their aircraft into places and situations where radio-controlled flight had never been contemplated: landmarks, public parks, events and festivals, and so on. It did not take long for these activities to evolve into commercial operations, as these pilots could provide aerial imaging at a tiny fraction of the cost of a conventional aircraft, or even in environments that would be impossible by any other means.

To guide their operations, these industry pioneers referred back to AC 91-57 and complied with its recommendations. The FAA viewed this as going well beyond the intention of the original advisory circular, so in 2007 the agency released docket number FAA-2006-25714, clearly stating that commercial operations were not permitted under the auspices of AC 91-57.

FAA Prohibits UAS Operations

Effectively, the FAA’s action outlawed all private, commercial UAS operations in the United States. Public entities, such as a fire department or law enforcement agency, could seek a Certificate of Authorization (COA) from the FAA to permit limited operations, but these were difficult and time-consuming to acquire—and were not available to private individuals or businesses. Nevertheless, innovation continued among hobbyists and companies operating overseas, beyond the reach of US regulatory authorities.

Through these efforts, aircraft became more capable, more reliable and less expensive. In spite of the FAA’s blanket prohibition, commercial activities continued to expand, with some operators openly advertising their services on the Internet. Especially in film and television production, UAS operations were becoming increasingly common. By providing no legitimate means to permit such operations, the FAA had created a pressure vessel without an emergency relief valve—and the overwhelming market demand for this technology threatened to burst the regulatory framework meant to contain it.

When Congress passed the 2012 FAA Modernization and Reform Act (FMRA 2012), it opened the door to limited commercial operations in Section 333 of the law. It permitted the FAA to approve individual private operators on a case-by-case basis. However, it was 2014 before the agency actually took advantage of this clause and approved six “Section 333 exemptions” for aerial film crews based in Los Angeles.

The requirements to receive permission to operate under Section 333 were onerous. The person operating the drone had to be a licensed full-sized aircraft pilot and possess a Class 2 medical certificate—a standard even higher than is required for private pilots. Applicants for Section 333 exemptions had to submit voluminous paperwork related to their qualifications, maintenance procedures and safety protocols, and were limited to flights within a “sterile” environment on a movie or television production set.

Although Section 333 established a high standard—too high, in the estimation of many industry participants—it nevertheless provided a lawful avenue to conduct commercial UAS operations. Demand for Section 333 exemptions quickly spread beyond Hollywood to operators around the country interested in a portfolio of business opportunities beyond film and television production.

Part 107: Rise of the Drones

FMRA 2012 also set a 2015 deadline for the FAA to achieve “full integration” of UAS into the National Airspace System (NAS)—a goal that has not yet been accomplished, nor will be in the foreseeable future. However, the agency has achieved several important milestones: none more significant than the establishment of 14 CFR Part 107 in 2016, which puts in place a regulatory framework for widespread deployment of commercial drones.

Part 107 establishes a clear set of rules for drone pilots to follow. Highlights include:

- No operations at an altitude higher than 400 feet above ground level

- No operations in excess of 100 miles per hour

- No operations of an aircraft weighing 55 pounds, or more

- No operations at night or with less than three statute miles of visibility

- No operations above persons not directly involved in the flight

- The aircraft must remain within the pilot’s visual line of sight at all times

- Pilot must only operate one aircraft at a time

- The UAS must yield the right of way to all other aircraft

- Operations in uncontrolled airspace are permitted without authorization

- Operations in controlled airspace are permitted with authorization

Part 107 also established a standard for the qualification of drone pilots: a 60-question Airman Knowledge Test (AKT) administered in a manner identical to private pilots and every other rating established by the FAA. Applicants must pass with a minimum score of 70 percent and must re-test every two years in order to keep their certification current.

Most critically, the FAA acknowledged UAS as “aircraft”—no different under the law from Cessnas and 737s—and their pilots as full members of the aviation community. However, this created a regulatory paradox that persists even today. If a drone is an aircraft, defined as “a device that is used or intended to be used for flight in the air,” then so is a model airplane.

Drones and Model Airplanes

Complicating the matter further, in FMRA 2012, the AMA had achieved a long-standing goal of its lobbying efforts with Congress’s adoption of Section 336: the Special Rule for Model Aircraft. In short, it said that the FAA had no authority to create new rules governing model aircraft and shifting responsibility for their regulation to a community-based organization (CBO). Under the definitions in the law, only the AMA qualified as a CBO.

However, the FAA refused to acknowledge the AMA’s role as a CBO, arguing that the law did not define how a CBO would be formally recognized. This left the FAA as the sole arbiter of a critical distinction: between commercial and recreational operations. Ultimately, the FAA settled on a very broad definition of commercial operations, and a very narrow definition of recreational operations.

In essence, the FAA determined that UAS flights shall be considered commercial operations if they yield any benefit to any person, at the time of the flight or at any time in the future—regardless of whether or not money actually changes hands.

For example, if an unpaid search-and-rescue volunteer deploys a drone as part of a search for a lost hiker, that is a commercial operation because of the benefit to the hiker. If a farmer flies a UAS over her own fields to monitor the status of her crops, that is a commercial operation because those crops will eventually be sold for money. In theory, even capturing aerial video for fun and posting it on a personal Facebook page is a commercial operation, because Facebook will profit from the web traffic it generates. It is now settled, that to count as a recreational operation, a flight must be made purely for the enjoyment of the activity itself, in the moment it is occurring.

Going Backward

Not only has progress on UAS regulation been slow over the past decade, occasionally, it has even moved in reverse. One such example began in November 2015. Faced with the possibility of hundreds of thousands of new drones appearing under Christmas trees on the morning of December 25, the FAA used its emergency rule-making powers to establish a national system of UAS registration.

Under the system, all drone owners were required to visit an FAA website, pay a $5 registration fee and label their aircraft with a unique alphanumeric code. Failing to comply could result in a $27,500 civil penalty and criminal penalties up to $250,000 and three years in prison. Also, the regulation made no distinction between “drones” and “model airplanes,” so the traditional aeromodeling community was swept up in the effort, as well.

This action provoked a sharp response from the modeling community, centered on two key points: first, that the FAA had abused its emergency powers to sidestep the public comment period that is requisite in federal rule-making under the Administrative Procedures Act, and; second, the FAA was prohibited from putting in place new regulations affecting model aircraft under Section 336, the Special Rule for Model Aircraft. In spite of those protests, these registration regulations and penalties were put into effect and resulted in more than 700,000 registrations and allowing the FAA to take in more than $3.5 million from the new fee.

Opponents filed a lawsuit against the FAA, led by John Taylor—an attorney and drone enthusiast living in the Washington, D.C. area. In May 2017, an appeals court ruled in Taylor’s favor, holding that the FAA had indeed overstepped its authority and ran afoul of Section 336 in Taylor v. Huerta, 856 F.3d 1089 (2017).

Taylor’s victory proved to be short-lived, however. In January 2018, Congress enacted the National Defense Authorization Act, which included an amendment requiring all UAS to be registered with the FAA. With the requirement now written into law, it has become a permanent component within the industry. While registration remained unpopular with hobbyists, its reinstatement was welcomed by industry participants eager to see continued growth in the commercial use of drones. These included the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) and DJI, the world’s leading manufacturer of small, civil UAS, which saw registration as essential to the development of the market.

That same year, Congress passed the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (FRA 2018), which repealed Section 336 of FMRA 2012 and established in its place Section 349, giving the agency the explicit authority to regulate all UAS, including model aircraft flown for recreation. It also requires that all recreational UAS pilots pass an aeronautical knowledge test.

The test remains a work in progress as of this writing; however, early indications are that it will be much simpler than the test required to earn a certificate under Part 107, with the goal of insuring model aircraft and recreational drones do not interfere with the safe operation of manned aircraft.

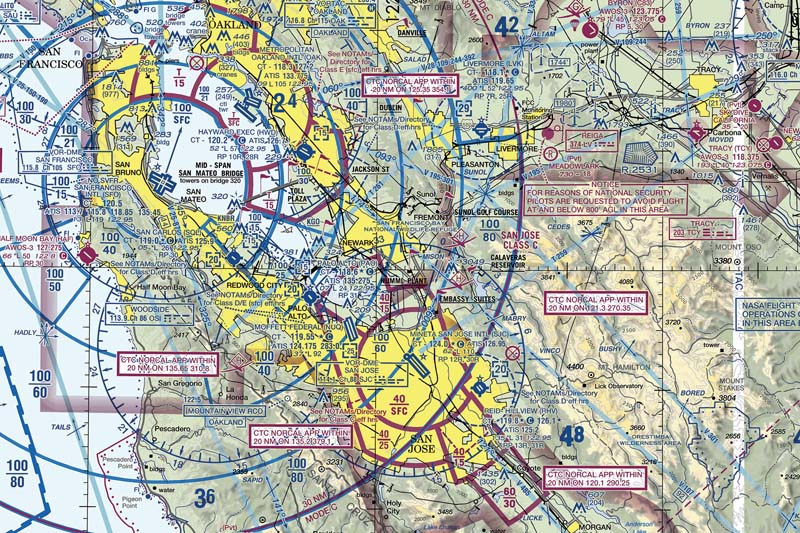

Drone pilots use maps like this of the San Francisco area to determine air space classifications.

Opening the Sky

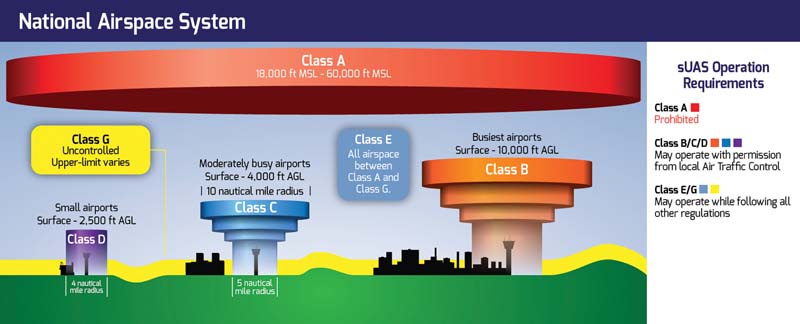

With drone operations now a recognized component of the National Airspace System (NAS), the FAA began work to provide better access to airspace for remote pilots. The division of airspace within the NAS is a complex subject. However, it can broadly be divided into two categories: controlled and uncontrolled. Uncontrolled airspace is typically found over rural, sparsely populated areas and exists between the surface of the Earth and an altitude not more than 1,200 feet above the local terrain elevation. Under Part 107, UAS pilots are permitted to operate in uncontrolled airspace without clearance.

Controlled airspace generally surrounds larger airports with an active control tower and tends to occur in more densely populated urban and suburban areas, where such airports are located. Any aircraft wishing to enter controlled airspace—be it a Boeing 737, a Cessna 172, or a 2-pound multirotor—must receive authorization. In the case of manned aircraft, this is accomplished by means of two-way radio communications with the control tower. However, the FAA was concerned that if UAS pilots sought authorization from local control towers via radio or telephone, air traffic controllers could become overwhelmed, to the detriment of their ability to manage crewed air traffic.

When Part 107 went into effect in 2016, the only method available to drone pilots for gaining authorization to operate in controlled airspace was to contact the FAA headquarters in Washington, D.C., via the agency’s website. The process was extremely cumbersome, and the minimum time required to receive authorization was about six weeks. Individually reviewing each request and performing a safety analysis also placed a heavy burden on the FAA’s staff. The need for a more efficient alternative was immediately apparent.

Free-LAANC Drone Pilots

In 2017, the FAA began prototype deployment of the Low-Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability (LAANC, pronounced “lance”) to solve this problem. LAANC divided up the controlled airspace around major airports into 1-mile squares and, based on an analysis of air traffic patterns at each site, assigned each of those squares a maximum altitude where UAS flight operations could be conducted safely without further analysis.

In keeping with the general requirements of Part 107, the maximum altitude for any square within a LAANC grid is 400 feet above ground level. Based on proximity to the airport and other factors, squares can also be assigned lower altitudes, such as 300, 200, 100, or even 50 feet above the surface—or zero, where drone flights are not permitted without further safety analysis.

To get authorization, drone pilots merely need to enter their credentials into a free app on their smartphone and request clearance to fly within a LAANC square with an altitude greater than zero. Within a few seconds, the request is recorded by the system and the pilot receives an automated text message, providing them with authorization to fly up to the indicated altitude.

After its basic functionality was proven in testing, LAANC was rolled out by regions, across the United States, over a seven-month period, beginning in April 2017. At present, LAANC grids are available for more than 600 controlled airports across the country and beginning in mid-2019, the FAA made the LAANC system available to recreational UAS pilots, as well.

Waivers, Not Regulations

The FAA has made no significant changes or additions to Part 107 since establishing it in 2016, nearly four years ago. Unlike crewed aviation, where pilots can receive a plethora of different ratings and certificates—recreational pilot, private pilot, commercial pilot, airline transport pilot, instrument-rated pilot, multi-engine pilot, and so forth—the Remote Pilot In Command (RPIC) certificate remains the only official status available for UAS operators.

Instead, the FAA has allowed operations that go beyond the scope of Part 107 through regulatory waivers issued to individual pilots or organizations. To qualify for a waiver, the applicant must submit a written plan through the agency’s website describing their intended operation, the procedures that they will follow and how safety will be assured. Once again, it is a slow, cumbersome process that must be completed for each individual application.

The “daylight operations waiver,” which ironically permits nighttime operations, is the overwhelming favorite, accounting for 89 percent of all waivers issued by the FAA. The remaining 11 percent are distributed among the following categories:

- Operating in controlled airspace that is not accessible through the LAANC system;

- Allowing a single pilot to control multiple UAS simultaneously (i.e., a drone swarm);

- Operating when visibility is less than three statute miles or in close proximity to clouds;

- Operating beyond the pilot’s visual line of sight (BVLOS);

- Operating above unprotected persons on the ground; and

- Operations from a moving vehicle or aircraft.

Several of these waiver types—including flying at night, beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) and over people—are capabilities regarded within the industry as essential if UAS are to achieve their full potential. BVLOS operations, for example, would be a huge benefit to activities such as linear infrastructure inspection: checking the length of a pipeline or high-tension power lines. Flights over people would allow for more effective applications in the media, academic studies and public safety.

However, rather than establishing a foundation of knowledge and a list of the minimum required equipment need to undertake each of these mission types safely, the FAA continues to require that each be assessed on a case-by-case basis—slowing the development of new capabilities and applications for commercial drones.

Remote Identification

The regulation of UAS is an ongoing process and, as of this writing, a major issue that has implications for the future of the industry is being decided. All serious participants in the commercial drone space agree that it is necessary to establish a system referred to as Remote Identification, also referred to as Remote ID, or RID. RID is meant to instill accountability among drone operators—in a manner similar to the way license plates hold drivers accountable. If a car is involved in a hit-and-run collision, witnesses can record the license plate and the police are then able to track down the offending vehicle and its occupant.

In crewed aviation, much the same mechanism exists. Each aircraft is assigned a unique alphanumeric tail number, and FAA regulations specify where and how large it must be displayed on every aircraft operating in the NAS. UAS present a unique challenge in this regard. While the FAA requires drone operators to display their registration numbers on an external surface of their aircraft, the aircraft themselves are so small that it cannot be discerned unless it is within arm’s reach. While this has some limited utility in identifying the pilot of a crashed drone, it does not offer the same functionality as a car’s license plate or an airplane’s tail number.

RID is universally viewed as a prerequisite to expanding commercial UAS operations, especially for operations BVLOS and in sensitive areas: near airports, power plants and other critical infrastructure.

The industry has largely achieved consensus that the solution to RID is for each drone to broadcast a unique radio signal, not unlike the transponder used on board crewed aircraft, that could be decoded using a dedicated system available to law enforcement, homeland security and FAA flight inspectors—or even a common smartphone. Were such a functional system available to the public through a smartphone app, it would reveal the drone’s registration number, which could then be given to authorities who would access a secure database to identify the pilot and take action, if necessary.

Beginning in 2017, Chinese drone manufacturer DJI unilaterally implemented a RID system on all of its drone aircraft. Simultaneously, it released the AeroScope: a product intended for use by government officials to identify and track drones built by the company. DJI also made the underlying protocols, which employ the same basic technology as wireless earphones, available to other drone manufacturers, as well—in an effort to establish a de facto industry standard, today known as “broadcast ID.”

This approach was accepted by industry and seemingly endorsed by Congress, as well. In 2016, it directed the FAA to establish a consensus standard for RID, resulting in the formation of a 74-member Aviation Rule-Making Committee (ARC). In spite of the fact that the committee was weighted heavily with representatives of law enforcement and other agencies that would bear responsibility for identifying and tracking wayward UAS, it ultimately endorsed broadcast ID as its favored approach, with an optional system tied to the cellular network.

According to the ARC’s final report, broadcast ID was favored because it would be inexpensive and easy to install on existing drones, achieve widespread compliance among pilots and offer robust performance. The cellular option was described as expensive, burdensome and potentially intrusive on a pilot’s privacy. European regulators agreed with this consensus judgment, and the FAA itself had been relying on broadcast ID for several years, using DJI’s AeroScope product to investigate and resolve incidents involving small UAS. So, broadcast ID appeared to be well-positioned to become the standard for RID.

Poorly Conceived, Poorly Received

Inexplicably, when the FAA announced its Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) pertaining to RID on December 31, 2019, it opted for a cellular-based system that would require drone pilots to subscribe to a private, third-party tracking service. In its NPRM, the FAA estimated the cost for such a service would be $2.50 per month. NERA Economic Consulting, a global financial analyst contracted by DJI to check the FAA’s numbers, put the cost at approximately $10 per month. Likewise, the FAA estimated a total economic impact of the rule’s passage at $582 million, whereas NERA put the cost at $5.6 billion. Although there is ample cause to be skeptical of both estimates, it is clear that the economic impact on individual operators and the industry as a whole would not be negligible.

In addition to the financial burden, the FAA’s Remote ID proposal would require significant new hardware, not currently integrated into any small, civil UAS now flying: of which there are about 1.3 million drone aircraft, at present. That entire fleet would presumably need to be grounded permanently. Also, since a cellular connection would be required for any flight operations, this could put drone aircraft out of service without warning in the event of a network failure, or flights occurring outside cellular coverage areas.

The FAA’s RID proposal also applies to most traditional aeromodelers, requiring their aircraft to incorporate the same cellular-based system as commercial drones, in most cases. There is an exception for established, fixed flying sites such as the model airfields affiliated with the AMA. However, the proposal does not put in place any mechanism to add new fields to the current inventory and anticipates that the number of modelers’ fields will diminish over time—eventually becoming extinct. In addition to the financial burden it would put on hobbyists, there are entire categories of model airplanes and helicopters are too small to incorporate the required technology.

Across the industry and the broader UAS community, the reaction to the FAA NPRM was swift and negative. DJI was joined by the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) and other companies and organizations in calling out the FAA’s RID proposal as expensive, burdensome, intrusive and likely to lower the rate of compliance with the final rule. The AMA declared that the rule poses an existential threat to traditional aeromodeling—requiring a monthly subscription for a child to play with a small model airplane occasionally in their own backyard, for example.

The AMA was supported in its strong rejection of the proposal by two organizations that represent primarily crewed aviation: the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) and the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA), both of which expressed concern that limiting childhood participation in aeromodeling would reduce the level of interest full-size aviation in the future.

FAA’s release of its RID NPRM was followed by a 90-day public comment period, which ended on March 3, 2020. In that time, it received more than 50,000 comments. A request from industry stakeholders to extend the comment period based on the high level of response was denied by the agency. At present, the FAA is reviewing the feedback it received as it must and is expected to announce its decision later this year.

Uncrewed Traffic Management

Working in partnership with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and other organizations, the FAA have been developing an air traffic control system for UAS—known as uncrewed traffic management (UTM). UTM will bring many benefits to the industry, including the possibility of routine flights beyond visual line of sight. The creation of UTM will require the identification of services, roles and responsibilities, data exchange protocols, performance requirements and so forth for low-altitude drone flights.

UTM will work in concert with LAANC so that drones are able to fly from place to place, from mission to mission, using a communication system composed of a network of automated systems accessed through application programming interfaces (API). Those dynamic interfaces will enable, guide and restrict movements to include imposing UAS volume restrictions (UVR), to avoid congested low-altitude airspace operations or other problems. On March 2, 2020, FAA distributed its Version 2.0 of the UAS Traffic Management (UTM) Concept of Operations (ConOps 2.0). A key focus of the Con Ops 2.0 is security and the full implementation of RID.

Federal Preemption

In law, the concept of federal preemption holds that an individual state, county or city cannot promulgate a law, regulation or ordinance that conflicts with the federal government’s own rules. This principle has been tested repeatedly as local jurisdictions create rules to govern the use of drones that run afoul of the FAA’s dominion over the NAS. The resulting legal decisions have created bright line separation between the FAA and local governments, as well as some important gray areas.

On December 17, 2015, the FAA chief counsel published “State and Local Regulation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Fact Sheet” that outlined the lines of authority. This document features prominently in FAA’s commentary to its own regulations under Part 107. Among other things, the fact sheet:

“[S]ummarizes well-established legal principles as to the Federal responsibility for regulating the operation or flight of aircraft, which includes, as a matter of law, UAS. The Fact Sheet also summarizes the Federal responsibility for ensuring the safety of flight as well as the safety of people and property on the ground as a result of the operation of aircraft.

“Substantial air safety issues are implicated when State or local governments attempt to regulate the operation of aircraft in the national airspace. The Fact Sheet provides examples of State and local laws affecting UAS for which consultation with the FAA is recommended and those that are likely to fall within State and local government authority.”

The fact sheet makes clear that FAA is in charge of drone flights, training and equipage and that before state or local governments attempts to regulate in these areas, they would be well-advised to consult with FAA to ensure that state and local governments do not overstep.

However, the fact sheet also states that state and local government are responsible for “Laws traditionally related to state and local police power, including land use, zoning, privacy, trespass, and law enforcement operations”; “requirement for police to obtain a warrant prior to using a UAS for surveillance;” “specifying that UAS may not be used for voyeurism”; “prohibitions on using UAS for hunting or fishing, or to interfere with or harass an individual who is hunting or fishing”; and “prohibitions on attaching firearms or similar weapons to UAS.”

Confirming the FAA’s Authority

In at least one instance, the courts have already shown deference to the FAA as regards the operation of UAS in the context of local regulations: Singer v. City of Newton, 284 F.Supp 125, (2017). The plaintiff in this case, Dr. Michael Singer, is a physician and professor at Harvard University. A drone enthusiast and certified pilot under Part 107, Dr. Singer sued when his home town of Newton passed an ordinance requiring all UAS to be registered with the city and banned flights at an altitude below 400 feet above private property without the expressed permission of the owner, among other provisions.

The court agreed with Singer that the ordinance was preempted by federal law. The court observed that since the FAA only allows drone flights at an altitude of 400 feet and below, the ordinance effectively banned drones in the city, when both congress and the FAA were charged with integrating drones into that same airspace. The city appealed the decision, but later asked for its appeal to be dismissed—a motion granted by the court.

By Wendie Kellington & Patrick Sherman

Patrick Sherman is a pioneer in the drone industry and founder of the Roswell Flight Test Crew. A popular writer and speaker across the industry, he is an adjunct faculty member of the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide Campus Department of Flight. A drone pro with the Federal Aviation Administration Safety Team (FAAST), he has been recognized as the drone instructor of the year by the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI).

Wendie Kellington, Esq., is the principle attorney at the Kellington Law Group in Lake Oswego, Oregon. An expert in land-use issues, she has expanded her practice over the past decade to providing advice and guidance regarding the legal use of uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS). She has advised the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) on regulatory issues and is a board member of the AUVSI Cascade Chapter.